Scientists Discover One of the Universe’s Largest Spinning Structures — A 50-Million-Light-Year Cosmic Thread

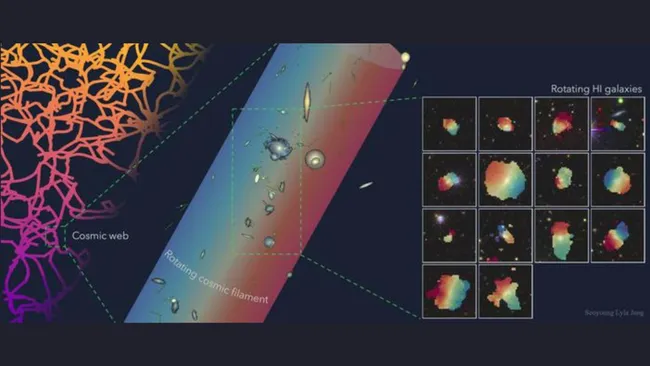

Scientists have identified one of the largest known rotating structures in the universe: a gigantic cosmic thread stretching 50 million light-years. Galaxies embedded inside this immense dark matter filament were found to be spinning in the same direction as the filament itself. This finding challenges long-standing assumptions about how a galaxy’s surroundings influence its evolution.

The filament is part of the cosmic web, a vast structure composed primarily of dark matter with ordinary matter woven throughout it. This web spans the observable universe. The newly studied filament is located about 140 million light-years from Earth and contains a layered structure. At its core lies a precise row of 14 galaxies arranged in a narrow line measuring 5.5 million light-years in length and about 117,000 light-years in width. These galaxies are rich in hydrogen gas, which is essential for star formation. This inner row is embedded within the much larger filament, which is 50 million light-years long and contains roughly 300 galaxies in total.

What makes this row of galaxies remarkable is not simply their linear alignment, but the fact that many of them rotate in the same direction as the filament itself. Each galaxy spins on its axis while also rotating around the long axis of the filament at approximately 68 miles per second, or 110 kilometers per second. This coordinated motion makes the structure one of the largest known cohesive rotating systems in the universe.

“What makes this structure exceptional is not just its size, but the combination of spin alignment and rotational motion,” said Lyla Jung of the University of Oxford. She compared the motion to a theme park teacup ride, where each teacup spins individually while the entire platform rotates simultaneously. According to Jung, this dual rotation provides rare insight into how galaxies acquire their spin from the larger cosmic structures they inhabit.

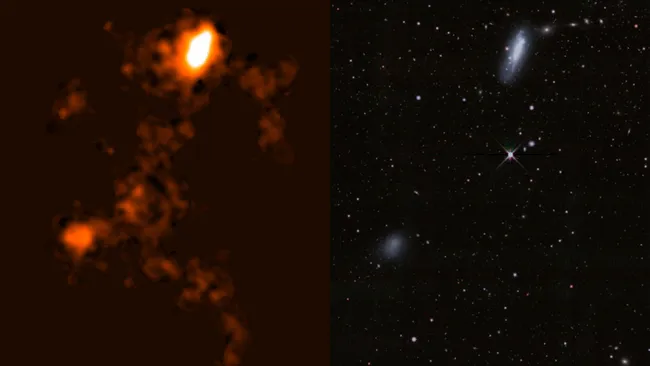

The research was led by Jung and Madalina Tudorache, also from the University of Oxford. Their team used the 64 connected radio dishes of the MeerKAT telescope in South Africa to track the movement of neutral hydrogen gas within both the galaxies and the filament. This data was combined with optical observations from the Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument at the Kitt Peak National Observatory in Arizona and from the Sloan Digital Sky Survey in New Mexico.

In 2022, astronomers had already established that filaments within the cosmic web rotate based on the motion of the galaxies inside them. However, the new finding that individual galaxies also spin in the same direction as the rotating filament was unexpected. This conflicts with prevailing theories of galaxy formation, which suggest that a galaxy’s spin is largely inherited from the original cloud of gas that formed it billions of years ago.

In the Milky Way, for instance, gas, dust, and stars rotate around the galactic center. The sun requires about 220 million years to complete a single orbit. Although this spin originates from the early angular momentum of the galaxy’s birth cloud, most galaxies later undergo close encounters, collisions, and mergers that disrupt their original rotation.

In this newly discovered filament, however, the dominant influence appears to be the filament’s own rotation. The filament may be channeling hydrogen gas along its dark matter framework and into the galaxies in a way that enforces their spin direction while also supplying fresh material for star formation.

“This filament is a fossil record of cosmic flows,” Tudorache explained. She stated that it helps researchers reconstruct how galaxies gain their spin and grow across cosmic time.

The galaxies within the filament also appear to be relatively young and still in early stages of development. Their rotational behavior could still change as they evolve further. Even so, the degree to which material flows along cosmic filaments can shape galaxy properties was not previously expected to be this strong.

These alignments may also affect measurements conducted in weak gravitational lensing surveys, such as the upcoming Legacy Survey of Space and Time at the Vera C. Rubin Observatory in Chile. Weak lensing studies analyze subtle distortions in galaxy shapes caused by dark matter to map the cosmic web. A deeper understanding of how galaxies align and rotate within filaments will be essential for improving the accuracy of these cosmic measurements.