Europe has just run its most extreme space weather simulation yet — a catastrophic solar storm so intense that no spacecraft would survive the event.

The European Space Agency (ESA) conducted the simulation at its Mission Control Center in Darmstadt, Germany, testing how satellites and operations teams would respond to a solar superstorm comparable to the 1859 Carrington Event, the most powerful geomagnetic storm ever recorded. The goal: to evaluate space weather preparedness ahead of the upcoming Sentinel-1D mission, scheduled for launch in November.

“Should such an event occur, there are no good solutions. The goal would be to keep the satellite safe and limit the damage as much as possible,” said Thomas Ormston, Deputy Spacecraft Operations Manager for Sentinel-1D, in an ESA statement.

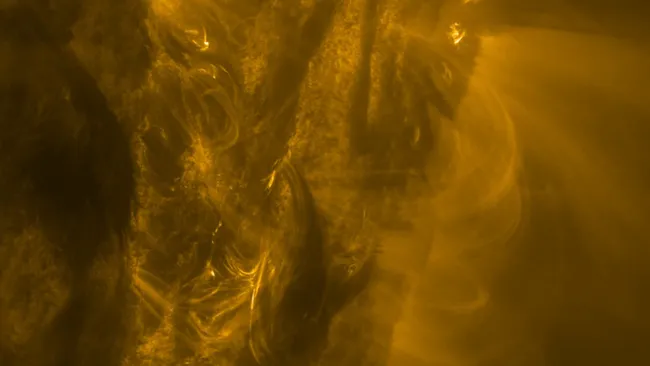

In the simulation, the Sun unleashed a triple threat. First came an enormous X-class solar flare, striking Earth within eight minutes and disrupting communications, radar, and tracking systems. A subsequent barrage of high-energy protons, electrons, and alpha particles hit satellites in orbit, causing false readings, corrupted data, and possible hardware damage.

Fifteen hours later, a massive coronal mass ejection (CME) slammed into Earth’s magnetic field. The planet’s upper atmosphere swelled, increasing satellite drag by up to 400%, disrupting orbits, raising collision risks, and shortening satellite lifespans.

On the ground, such a storm could overload power grids and pipelines with geomagnetic energy. The exercise forced ESA controllers to make real-time decisions, offering insight into how to manage operations when space weather turns catastrophic.

“The immense flow of energy ejected by the Sun may cause damage to all our satellites in orbit,” said Jorge Amaya, ESA’s Space Weather Modelling Coordinator. “Even low-Earth orbit satellites, typically shielded by our atmosphere and magnetic field, would not be safe during an event of Carrington magnitude.”

The simulation revealed how a severe solar storm could trigger a chain reaction — satellite failures, navigation degradation, and total loss of critical communications. ESA scientists warn that such an event is not hypothetical but inevitable.

“The key takeaway is that it’s not a question of if this will happen, but when,” said Gustavo Baldo Carvalho, Lead Simulation Officer for Sentinel-1D.

To prepare for the unavoidable, ESA is expanding its solar monitoring network and gearing up for the 2031 Vigil mission, a spacecraft that will operate at the Sun–Earth L5 point to provide early warnings of incoming solar eruptions. Officials emphasize that the goal is to ensure faster recovery for both spacecraft and ground infrastructure when the next solar catastrophe strikes.