After three years of observing known exoplanets, the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) has now achieved a major milestone: the discovery and direct imaging of its first new exoplanet.

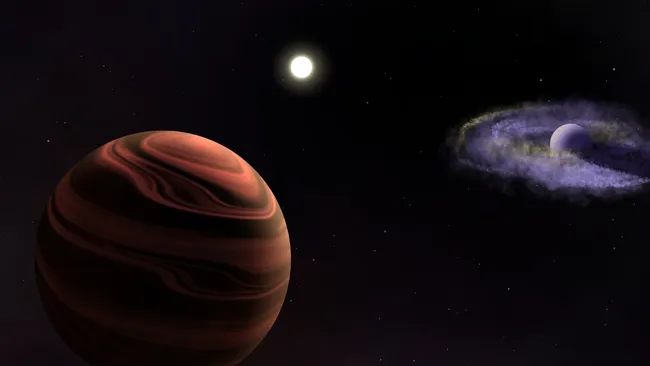

Named TWA 7b, this planet is located about 111 light-years from Earth and orbits a young, low-mass star called CE Antliae, also known as TWA 7. What makes TWA 7b especially remarkable is that it holds the record for being the lowest mass exoplanet ever directly imaged. With an estimated mass of just 100 times that of Earth — about 0.3 times the mass of Jupiter — TWA 7b is roughly ten times lighter than any other directly imaged exoplanet to date.

CE Antliae, the star around which TWA 7b orbits, is just a few million years old — a cosmic newborn compared to our 4.6-billion-year-old Sun. Since its discovery in 1999, CE Antliae has fascinated astronomers, especially because it’s viewed pole-on from Earth, offering a rare top-down view of its protoplanetary disk — the dusty rings of debris where planets form.

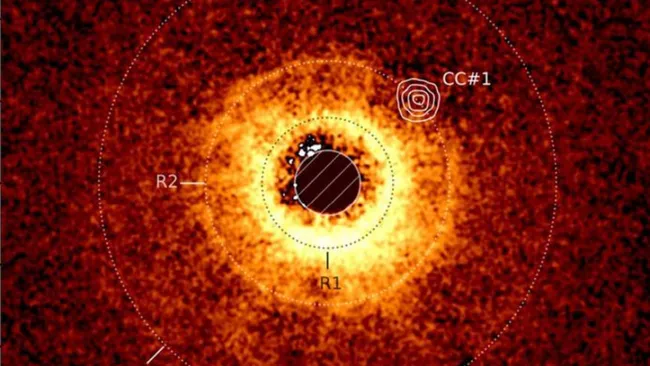

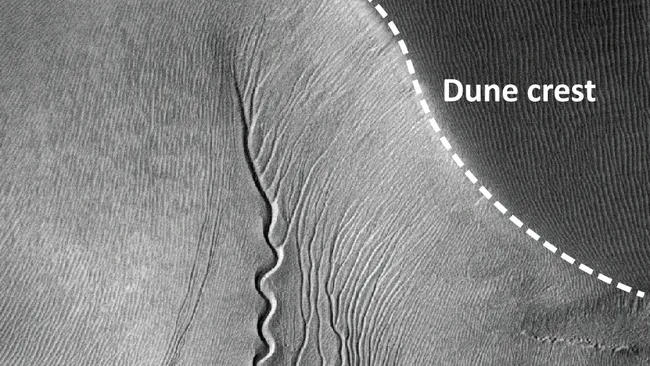

These rings are particularly telling. JWST spotted three distinct debris rings around the star. One ring, in particular, stood out: a narrow band bordered by two gaps largely free of material. When the telescope imaged this area in infrared light, it detected a bright source, which astronomers identified as a likely exoplanet.

To confirm the discovery, the research team ran simulations showing that a planet of TWA 7b’s size and orbit could create the same ring-and-gap structures observed — supporting the conclusion that the object is indeed a planet, and a young one at that.

JWST’s Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI) was crucial to this discovery. TWA 7b, being young and relatively low in mass, emits infrared radiation, which is precisely the wavelength JWST is built to detect. Normally, the light from a planet’s host star would overwhelm such faint signals, but JWST uses a coronagraph, a special tool that blocks out the star’s light, making the planet’s glow detectable.

This historic find marks not only JWST’s first planetary discovery, but also a new era in imaging smaller and lighter exoplanets. With its unmatched sensitivity and resolution, JWST is expected to identify many more worlds in the years ahead — some even smaller and potentially more Earth-like.

The findings were published in the journal Nature.