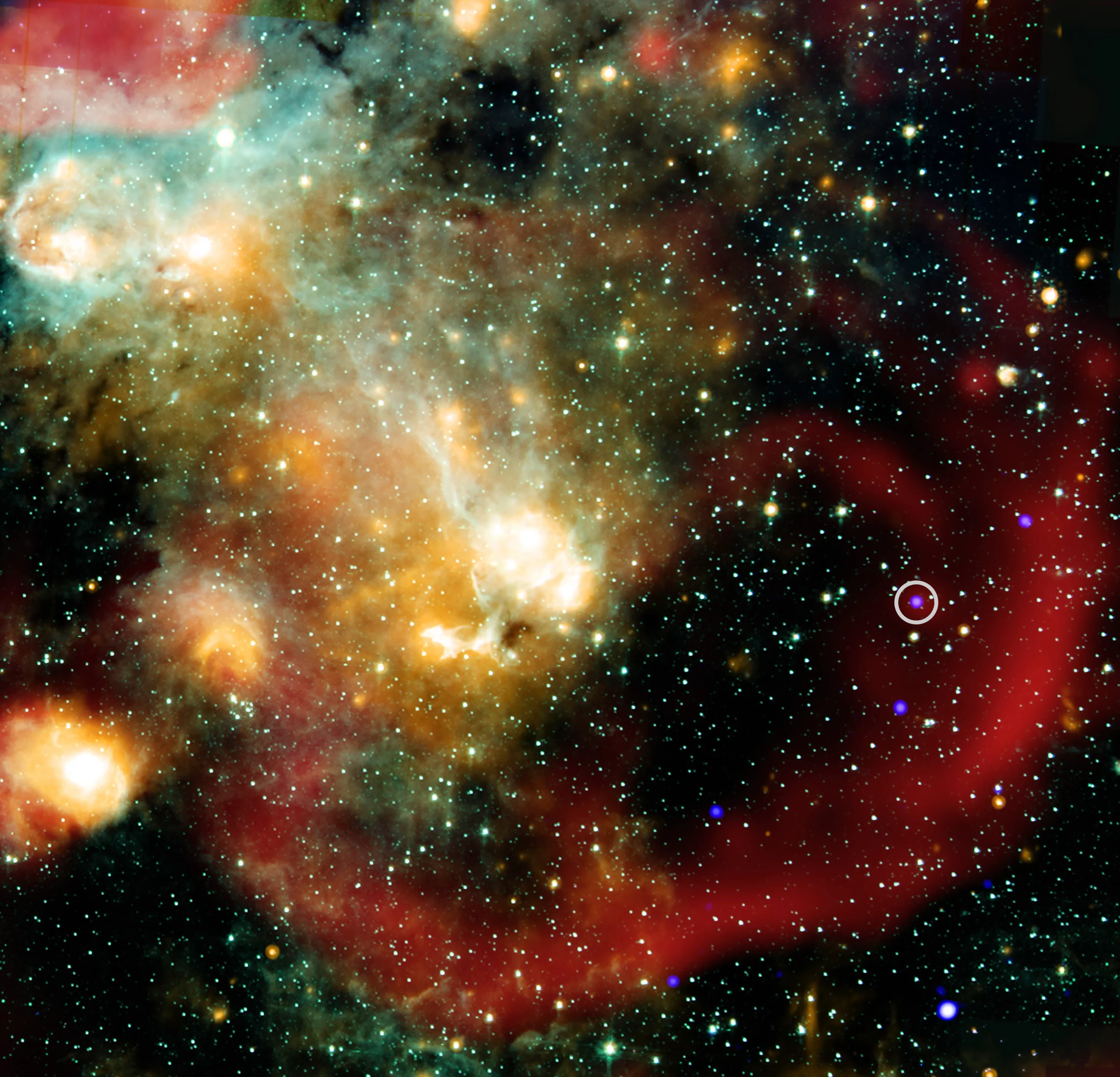

Astronomers have just taken the most detailed peek yet into a galaxy cluster that lies 800 million light-years from Earth — and what they found is nothing short of astonishing. Dubbed Abell 2255, this enormous cluster spanning 16.3 million light-years is home to hundreds of galaxies, many of them in the process of colliding. But it’s the colossal cosmic tendrils emerging from them that have stunned scientists.

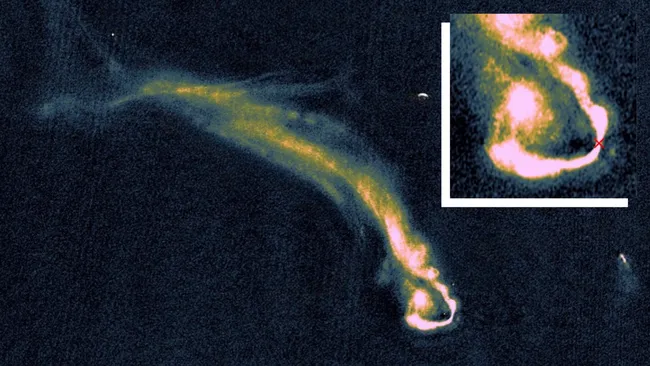

Using the European LOFAR radio telescope in its ultra-sharp VLBI mode, researchers captured 56 hours of radio observations. The result: images so crisp they unveiled filaments — thin strands of matter — stretching up to 360,000 light-years across space. To put it in perspective, that’s over three times the width of our own Milky Way galaxy.

What’s even more puzzling is the nature of these filaments. Barely a tenth the thickness of the Milky Way, these radio-bright tendrils seem to stream from galaxies fueled by supermassive black holes. These so-called “radio galaxies” eject jets of matter at nearly light speed, sculpting structures previously invisible to us.

“We aimed to detect filaments in the tails of radio galaxies inside Abell 2255,” explained Emanuele De Rubeis from the University of Bologna. “Modern tools like LOFAR-VLBI are finally allowing us to observe the magnetic and energetic makeup of these structures.”

Among the most intriguing objects is the “Original Tailed Radio Galaxy,” which displayed tangled trails and rich textures unseen in prior surveys. Other galaxies — colorfully nicknamed Goldfish, Beaver, and Embryo — also exhibited dramatic tails over 200,000 light-years long.

These bizarre structures are thought to be drawn out by turbulent intergalactic motions. Over time, they may merge with the vast sea of dust and gas that floats between galaxies, known as the intergalactic medium. Scientists believe studying these features may reveal how black hole-driven jets evolve and interact with their galactic surroundings.

Behind this discovery lies enormous technical effort. Each night of observation generated around 4 terabytes of data. After processing and calibration — which involved months of work — that figure jumped to nearly 140 terabytes. The result, however, was worth the effort.

Published in Astronomy & Astrophysics on June 10, this breakthrough doesn’t just offer a window into one galaxy cluster — it may reshape how we study the invisible skeleton of the cosmos.

Want to see what the universe is hiding in plain sight? The full paper is now available, offering the most complete view yet into one of the most mysterious clusters in deep space.