Modern science can now narrow down potential oil reserves with notable precision, particularly in the case of shale oil embedded within sedimentary rock. Research conducted in China’s Sichuan Basin shows that changes in Earth’s orbit can help predict where shale oil is most likely to develop.

Unlike conventional crude oil that gathers in underground reservoirs, shale oil remains trapped inside shale rock. Shale forms from thin layers of fine sediment deposited in ancient lakes or seas. Low oxygen conditions allow organic matter to build up and gradually transform into oil over millions of years.

For a long time, shale oil reserves were difficult to locate due to limited understanding of shale formation. This new study addresses a critical gap by clarifying how environmental changes shaped these rocks.

Researchers combined elemental data from Earth’s crust and mantle, observations from rock cores, and natural gamma-ray measurements from Jurassic-age lake mudstones. Using this approach, they reconstructed how environmental conditions evolved over time.

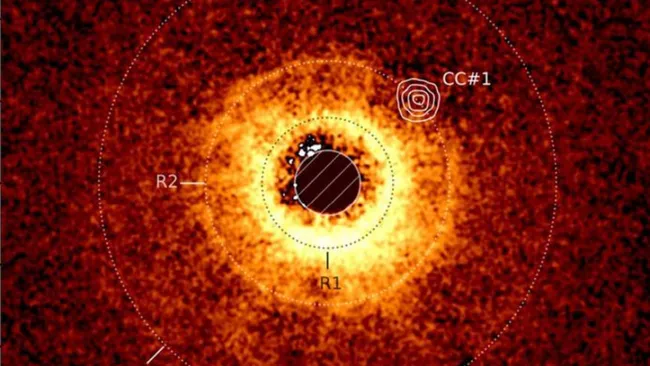

The results revealed a strong connection between sediment changes and Milankovitch cycles. These cycles describe regular variations in Earth’s orbit and axial tilt that influence long-term climate patterns, including ice ages.

One key factor is orbital eccentricity, which refers to the stretching and tightening of Earth’s elliptical orbit. This cycle unfolds over hundreds of thousands of years and plays a major role in climate variation.

Rock records showed that periods of high eccentricity produced stronger seasonal contrasts. Warmer and wetter conditions increased nutrient flow into lakes, boosting biological productivity.

This process led to the formation of finely layered, organic-rich mudstones. These rock types are considered the most favorable environments for shale oil formation.

When orbital eccentricity declined, climate conditions became drier. Lake levels fell, sediment transport shifted, and sand-rich deposits spread across basin slopes and into deeper areas through gravity-driven flows.

The alternation between wet and dry phases created a consistent stacking pattern of rock layers across the basin. This predictable structure provides valuable clues for shale oil reserves prediction.

The study also found that sediment accumulated at an average rate slightly above four centimeters per thousand years. This slow buildup allowed scientists to align individual rock layers with specific orbital cycles.

Based on these findings, researchers developed a new framework to identify high-quality shale reservoirs more effectively. The method improves accuracy in targeting potential shale oil reserves.

It is important to note that shale oil extraction relies on hydraulic fracturing, a process associated with environmental concerns. Despite this, oil remains a major global energy source during the transition to renewable alternatives.

By combining astronomy with geology, scientists are uncovering new ways to understand Earth’s history and locate critical energy resources. Earth’s orbit and oil reserves are now more closely linked than previously understood.