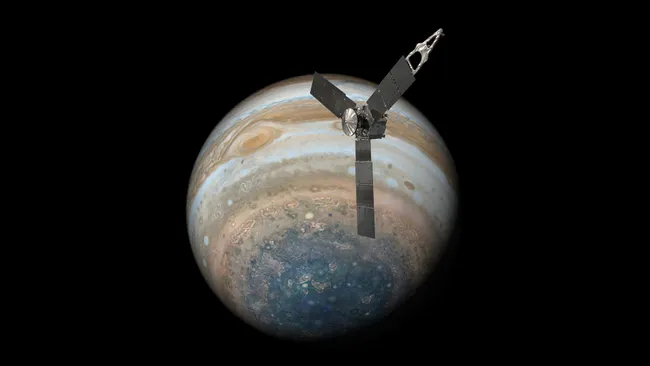

Space debris has become an increasingly serious threat as human activity in orbit continues to expand. China regularly sends astronauts to and from its Tiangong space station. However, one recent mission highlighted how fragile space operations have become.

The Shenzhou-20 crew capsule was scheduled to undock and return to Earth. The journey was anything but routine. The capsule carried no astronauts after one of its windows was struck by space debris. During pre-return inspections on November 5, astronauts observed what appeared to be a crack in the glass.

Space journalist Andrew Jones explained that ground-based experts analyzed images of the damage. Their conclusion pointed to a debris fragment smaller than one millimeter that penetrated both the outer and inner layers of the window. Despite its size, the debris caused significant structural damage.

Simulations and physical testing indicated a low probability of window failure during atmospheric re-entry. Re-entry exposes spacecraft to extreme temperatures and stress. Even with the low probability, officials determined the risk was unacceptable. A rescue mission, Shenzhou-22, was launched to safely return the astronauts from the station.

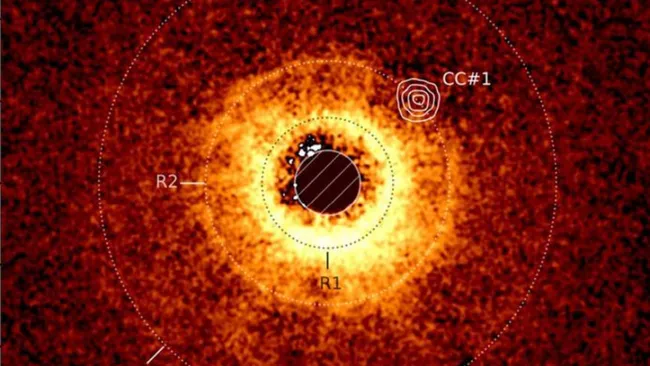

Experts have warned for years about the growing space debris threat. The rapid expansion of government and private space programs has created a congested orbital environment. The European Space Agency estimates more than 15,100 tonnes of human-made material orbit Earth.

There are approximately 1.2 million debris objects measuring between one and ten centimeters. An estimated 140 million pieces range from one millimeter to one centimeter. In low Earth orbit, these objects travel at around 7.6 kilometers per second. At such speeds, even tiny fragments can cause severe damage.

This reality explains how debris smaller than one millimeter breached the reinforced glass of the Shenzhou-20 capsule. As orbital congestion increases, similar incidents are expected to occur more frequently. Equipment damage is costly, and the risk to human life continues to rise.

When debris strikes another object, it can generate additional fragments. This chain reaction worsens the orbital debris problem. While several countries track objects in space, information sharing remains limited. Many satellites are classified, which discourages transparency.

China’s space program operates under military oversight, reflecting the view that space activity is closely tied to national security. This approach adds another layer of geopolitical tension to space governance. These tensions complicate international cooperation on debris mitigation.

The 1967 Outer Space Treaty attempted to define how space should be governed. However, the treaty does not address modern challenges. It fails to account for private launches, increased debris, or sustainable orbital use.

Although 117 countries are party to the treaty, enforcement mechanisms are weak. Organizations such as the Inter-Agency Space Debris Coordination Committee provide research platforms. They do not create binding obligations for states. The absence of enforceable global rules makes debris management far more difficult.

Several technological solutions have been proposed. Many exist only as conceptual missions with limited testing. One proposal involves harpoons designed to capture large debris. However, recoil could turn the capturing spacecraft into debris itself.

Another proposal uses large nets to slow debris. Slowed debris would re-enter the atmosphere and burn up. While effective in theory, these missions lack sustainability. Launching satellites to remove only a few objects consumes fuel and contributes indirectly to climate change.

A more efficient solution may involve satellite constellations dedicated to debris removal. These systems would remain in orbit and gradually de-orbit debris. This concept remains under research and development.

Ground-based approaches include laser broom systems. These use laser pulses to slow orbiting debris. Slowed objects could re-enter the atmosphere naturally. However, this technology remains untested and carries risks such as atmospheric heating and targeting errors.

Without resolving the geopolitics of space governance, debris removal efforts remain limited. National interests, security concerns, and private sector expansion are accelerating orbital pollution faster than cleanup efforts can respond.

History shows how quickly debris can multiply. In 2007, China destroyed its Fengyun-1C satellite during an anti-satellite test. The event created an estimated 3,500 debris fragments. In 2009, Russia’s Kosmos 2251 collided with an Iridium satellite, producing about 2,400 pieces.

In 2021, Russia conducted another anti-satellite test, destroying Kosmos 1408. The test generated 1,787 debris fragments. While many re-entered the atmosphere, roughly 400 pieces remained in orbit.

Repurposing anti-satellite weapons for debris removal remains unlikely. However, the concept carries theoretical potential. Meaningful progress will require global cooperation and transparency.

States and private companies must disclose orbital assets. Future spacecraft should be de-orbited at the end of their operational life. This commitment is essential to reduce long-term debris growth.

European Space Agency standards require satellites to be de-orbited within 25 years after mission completion. These rules also apply to small satellites such as CubeSats. However, reliable de-orbit methods for them have yet to be demonstrated.

Ultimately, space debris threatens all space agencies and commercial operators. Ground-based tracking systems have limitations. This reality makes global space governance unavoidable. It may take the loss of high-value satellites, or even human lives, before space debris is treated as a critical international issue.