Scientists have successfully moved closer to resolving an enduring puzzle in physics—the very existence of matter in the cosmos—thanks to a recently integrated analysis from two of the world’s foremost neutrino experiments.

By pooling almost 16 years of measurements, the NOvA experiment in the United States and the NOvA and T2K Experiments in Japan have produced the most precise view yet of how neutrinos and their antimatter counterparts transform during their travel. The findings, published on Oct. 22 in the journal Nature, refine the quest for subtle variations in how these particles behave—differences that could potentially explain why matter triumphed over antimatter in the early universe, known as the Matter-Antimatter Asymmetry.

If perfect symmetry existed, as described by the Standard Model of particle physics, the Big Bang should have created equal quantities of matter and antimatter nearly 14 billion years ago. Since matter and antimatter annihilate upon contact, a perfectly balanced universe should have resulted in a realm of pure energy. Yet, today’s cosmos consists overwhelmingly of matter, suggesting some subtle, still-mysterious mechanism granted matter a slight advantage early on.

A prime candidate for tipping these cosmic scales is the neutrino, a faint, nearly massless particle that saturates the universe but rarely interacts with anything. This characteristic leads scientists to frequently dub them “ghost particles.” Physicists have long speculated whether neutrinos and antineutrinos exhibit distinct behaviors that experiments can detect. Even a subtle mismatch, scientifically known as Neutrino CP Violation, could clarify how matter achieved its cosmic dominance.

“While there remains more to comprehend, the crucial experimental question is obvious: can we observe this symmetry violation in neutrinos, and if so, what is its magnitude?” Ryan Patterson, a physics professor at the California Institute of Technology and co-lead of the NOvA team, informed Space.com.

Neutrinos Change ‘Flavor’

Part of what makes neutrinos so elusive—and so compelling—is their intrinsic ability to change identity. They exist in three “flavors,” and as they traverse space, they undergo Neutrino Flavor Oscillation among these types because each flavor is a complex blend of three mass states. As neutrinos travel, these underlying mass states shift, causing the particles to morph from one flavor to another.

“If you imagine the flavors as being like strawberry, chocolate, and vanilla, this would be akin to finding your strawberry ice cream cone having changed to chocolate on your journey home,” a recent Caltech statement clarifies. By tracking these flavor changes, scientists can measure the minute mass differences that govern Neutrino Flavor Oscillation—and by comparing the behaviors of neutrinos with antineutrinos, they can probe for Neutrino CP Violation.

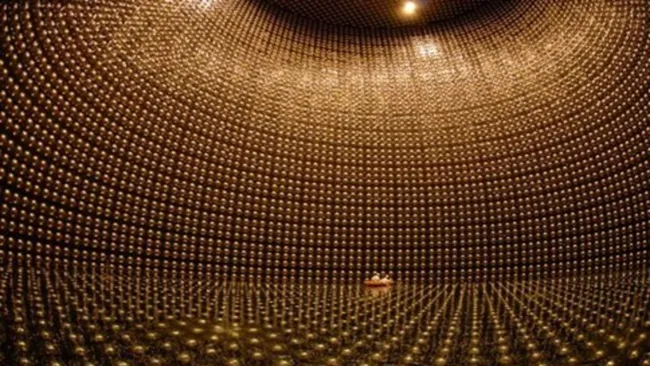

To accomplish this, the NOvA experiment (short for NuMI Off-axis $nu_e$ Appearance) shot a beam of neutrinos from Fermilab near Chicago toward a detector located 500 miles (800 kilometers) away in Minnesota. Across the Pacific, Japan’s T2K (short for Tokai-to-Kamioka) experiment transmitted its own beam 183 miles (295 kilometers) from the Japan Proton Accelerator Research Complex in Tokai to the immense Super-Kamiokande detector, buried 0.6 miles (about 1 kilometer) beneath a mountain in Kamioka.

Because the experiments operate at varying distances and energies, each captures complementary characteristics of neutrino oscillations. Combining their data permits researchers to isolate the subtle parameters controlling how neutrinos transform.

A key achievement of the joint analysis is a significantly refined measurement of one of the most fundamental oscillation parameters, known as the neutrino mass splitting. The collaboration has now constrained this value to merely 2 percent, establishing it as one of the most precise measurements ever reported by the NOvA and T2K Experiments.

“It is the foundation for all the other measurements we make,” Patterson stated. He added that this advance also creates pathways to determine the Neutrino Mass Hierarchy, the still-unknown arrangement of the three neutrino mass states.

“As of today, we accept the presence of three neutrino families, each linked to distinct masses,” Federico Sanchez, an experimental physicist specializing in neutrino physics and a longtime T2K collaborator, told Space.com. “But we still lack a fundamental understanding of why there are exactly three, not two, four, or more—and why their mass differences take the specific values we observe.”

“The Neutrino Mass Hierarchy is not only a crucial element for many theoretical calculations and predictions but also yields a tangible result that can be directly compared with existing models,” he added.

The mass hierarchy influences how neutrinos and antineutrinos oscillate differently—a key component of the search for CP violation. In what is termed the normal hierarchy, one of the three known neutrino “flavors,” muon neutrinos, transforms into electron neutrinos more readily than their antimatter counterparts, muon antineutrinos, transform into electron antineutrinos. In the inverted hierarchy, that pattern reverses.

The new joint analysis is not yet capable of confirming which hierarchy nature favors. But if future data suggests the hierarchy is inverted, Patterson says the current dataset already hints that neutrinos may violate CP symmetry. If that data confirms the normal hierarchy is correct, even more data will be required to distinguish the competing effects.

“Neutrino physics is a peculiar field. It is incredibly challenging to isolate effects,” Kendall Mahn, a professor at Michigan State University and T2K co-spokesperson, noted in the Caltech statement. “Combining analyses enables us to isolate one of these effects, and that signifies progress.”

A New Shared ‘Language’ for Neutrino Science

Beyond the immediate physics results, researchers claim one of the collaboration’s most significant accomplishments is the creation of an initial common framework—a shared “language” for how neutrino interactions are described across experiments.

Although all experiments are rooted in the same underlying physics, each makes differing approximations and methodological choices based on its unique detector design. Among the most critical assumptions are those concerning how neutrinos interact with matter, which is essential for accurately reconstructing their energy, and how many neutrinos are produced at a specific energy, said Sanchez.

Even minor differences in these models can impact the interpretation of Neutrino Flavor Oscillation patterns, he noted. By standardizing these assumptions, the collaboration has developed a starting template that future experiments can adopt to guarantee their findings are directly comparable, aiding in the ultimate resolution of the Matter-Antimatter Asymmetry.

“Precision in these measurements is vital, as even subtle discrepancies could signal departures from the model—potentially unveiling new physics,” Sanchez told Space.com. “The more precise the agreement, the more confident we are that our description is accurate.”

The timing is ideal. Scientists say such a unified framework will be indispensable for the next generation of ultra-sensitive experiments—the Deep Underground Neutrino Experiment (DUNE) in Illinois and South Dakota, and the Hyper-Kamiokande in Japan—which are currently under construction and slated to begin operations in 2028. These next-generation detectors will perform measurements far more sensitive than NOvA or T2K, potentially offering definitive evidence of CP violation in the next decade.

And if neutrinos genuinely do treat matter and antimatter differently, scientists may finally reveal the long-sought reason the universe exists in the form we observe today.