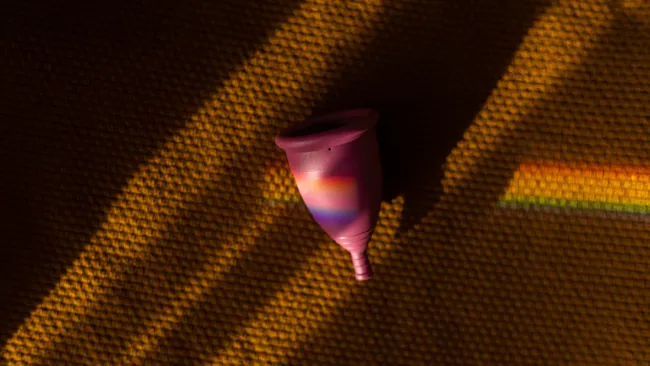

What happens if someone gets their period in space? Researchers have taken a step toward answering that question by experimenting with how a menstrual cup — a widely used reusable period product — performs under the intense conditions of space travel.

In 2022, a research team known as AstroCup sent two menstrual cups aboard an uncrewed rocket mission that lasted about nine minutes after liftoff and reached an altitude of approximately 1.9 miles (3 kilometers). The menstrual cups, produced by the brand Lunette, were exposed to vibration and other physical forces that could potentially compromise their structure or their ability to hold liquid. However, leak testing conducted with glycerol and water showed that the cups remained fully intact, with no structural damage or material degradation observed. The findings were recently published in the journal NPJ Women’s Health.

Menstrual cups are soft, reusable containers made from silicone that are worn internally during menstruation to collect blood. Their popularity has grown in recent years due to their sustainability compared with disposable products such as tampons and pads, since one cup can be used for several years. Although most astronauts who menstruate currently choose to suppress their cycles using hormonal methods, humanity’s expanding presence in space means that women will not always want — or be able — to pause their periods. In addition, spacecraft recycling systems were not originally built to process blood, and relying on disposable products can create extra waste and operational challenges.

Considering all these factors, the AstroCup researchers view menstrual cups as a promising solution for future missions and a major step toward improving health options in space. However, the study’s authors emphasized that additional research is needed to understand how menstrual cups perform in reduced gravity or during long-term missions, where removing the cup and handling its contents could be more complicated. To gather more data, the team hopes to send various menstrual products to the International Space Station for further testing and comparison.

“Now we can begin implementing and redefining health autonomy in space,” said astrobiologist Lígia Coelho, lead researcher of AstroCup, fellow at Cornell University’s Carl Sagan Institute, and lead author of the study, in a statement.

Why Astronauts Pause Their Periods — And Why That Won’t Always Work

Temporarily stopping menstruation by continuously taking birth control pills — skipping the placebo pills in a standard monthly pack — is considered safe for many people on Earth. It can even provide health benefits for individuals with certain conditions, such as severe endometriosis or premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD). There is no medical requirement to have a monthly bleed when taking hormonal contraceptives that suppress ovulation, which occurs when pills contain synthetic estrogen and progestin.

In space, this approach simplifies daily life for astronauts by eliminating the need to manage menstruation with hygiene products and may also reduce side effects of natural hormonal changes, such as cramps or fatigue. Other hormonal birth control options that reduce or stop menstrual bleeding altogether — including intrauterine devices (IUDs) — could also be used by astronauts, but research on how these methods perform in space does not yet exist. On Earth, progestin-only IUDs and implants like Nexplanon are associated with higher rates of breakthrough bleeding, especially during the first year of use, meaning they do not fully eliminate the need for menstrual products for all users.

Both on Earth and in space, additional estrogen carries potential risks, including an increased chance of blood clot formation, and a hormone-based regimen is not suitable for everyone. Combined oral contraceptives may also affect bone density, an issue that becomes even more significant in microgravity conditions and requires further study, as noted by the authors of the new research.

Although human reproduction and pregnancy in space remain theoretical and likely years away, the ability to effectively manage menstrual cycles during space missions will be essential if reproduction beyond Earth ever becomes a reality. Expanding menstrual management options could open new possibilities for long-term exploration.

“More women will have the opportunity to go to space for longer missions, and it is crucial that their autonomy over menstrual choices is respected,” the authors of the NPJ Women’s Health article wrote.

“Astronauts on future Moon and Mars missions may choose to continue menstruating for personal, health, or reproductive reasons.”