The James Webb Space Telescope has delivered major breakthroughs in understanding the early universe since it began operations in 2022. Despite this progress, the nature of dark matter has remained one of cosmology’s most persistent unanswered questions.

Dark matter is believed to make up around 85 percent of all matter in the universe. Scientists struggle to study it because it does not interact with light, or it does so extremely weakly, making direct detection nearly impossible.

This lack of interaction also confirms that dark matter is not composed of ordinary particles such as protons, neutrons, or electrons. These particles form everything visible, from massive stars to microscopic organisms.

Over the years, researchers have proposed many theoretical dark matter particles. However, none of these candidates has been directly observed, leaving their existence unproven.

Because dark matter cannot be seen directly, scientists detect it through its gravitational effects. Its presence is inferred by how it influences space, light, and the motion of visible matter.

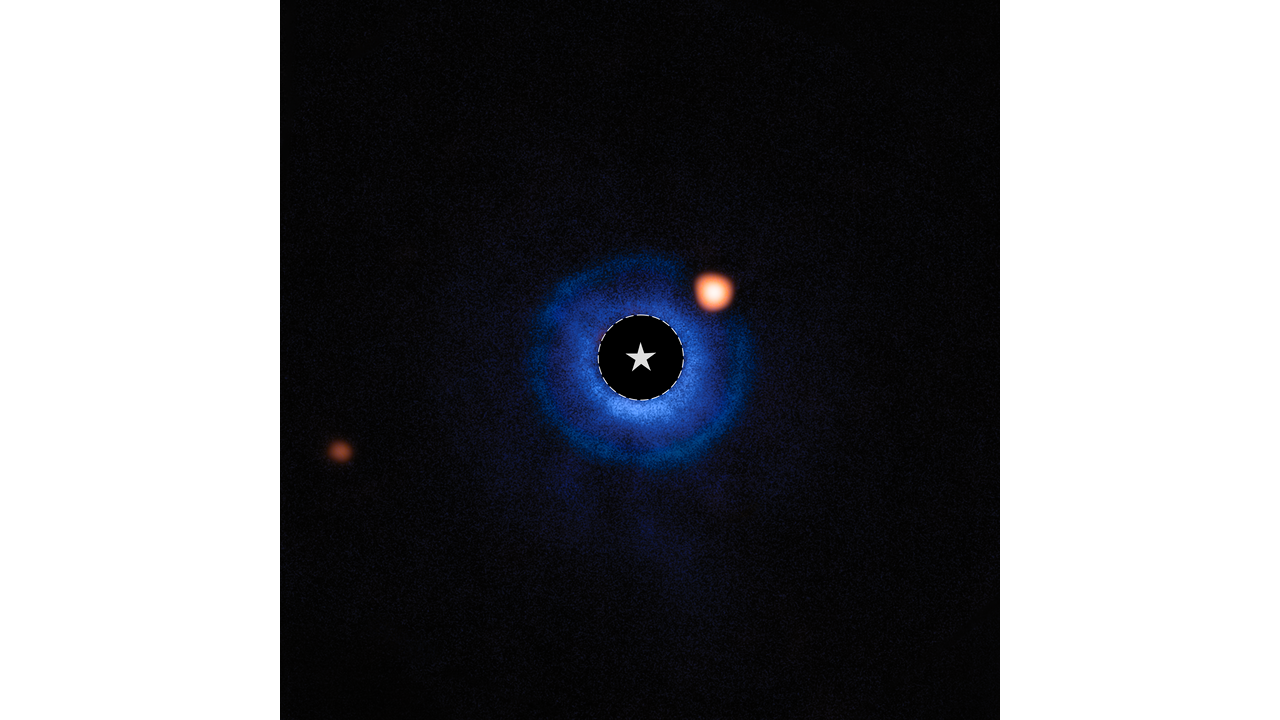

A new study published in Nature Astronomy suggests that dark matter’s gravitational influence may explain the unusual shapes of some very young galaxies. These galaxies appear far more elongated than current models predict.

Researchers propose that examining these stretched galaxies with the James Webb Space Telescope could help determine which theoretical dark matter particles are most plausible.

In the framework of general relativity, galaxies grow from small clumps of dark matter. These clumps form early star clusters that merge into larger systems through gravity.

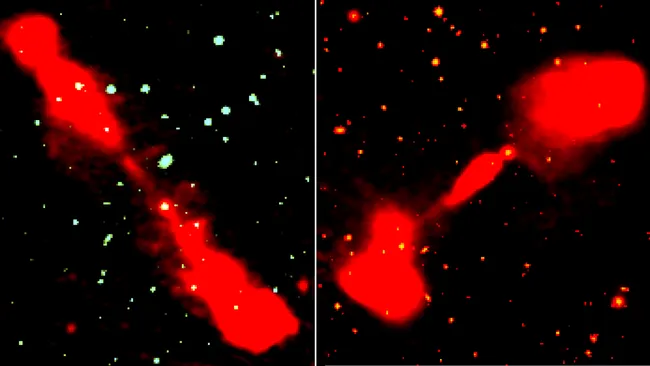

However, JWST observations indicate that some of the earliest galaxies may be embedded in filament-like structures. These structures differ from those predicted by traditional cold dark matter models.

According to the researchers, these filaments appear smoother and more continuous. Such behavior aligns more closely with theories involving ultralight dark matter particles that exhibit quantum properties.

These particles, sometimes described as “fuzzy dark matter,” behave like waves rather than individual particles. Their wave-like nature could suppress small-scale structures in the early universe.

Simulations show that if dark matter consists of ultralight axion particles, it would prevent very small structures from forming early on. This process could produce the long, smooth filaments observed by JWST.

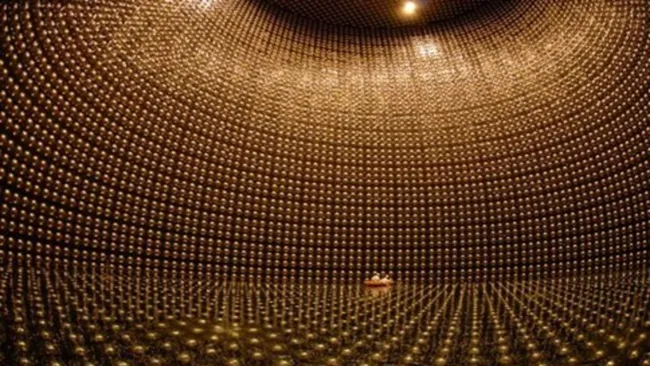

Researchers also examined models involving warm dark matter, such as sterile neutrinos. These faster-moving particles can also generate smoother filaments than cold dark matter.

In both scenarios, gas and stars gradually flow along these filaments. Over time, this process leads to the formation of elongated galaxies rather than rounder shapes.

The James Webb Space Telescope will continue observing strangely shaped galaxies from the early universe. Meanwhile, scientists on Earth are refining simulations that test different dark matter models.

Combining detailed JWST observations with advanced simulations may eventually narrow down the true nature of dark matter. This approach could bring researchers closer to solving one of the universe’s greatest mysteries.