At this very moment, you appear to be making a conscious decision to read this article. Yet physics states that every action must have a cause. This raises a troubling question about whether that decision was ever truly free.

One of the foundational ideas underlying all of physics is causal determinism. This concept holds that every effect arises from a prior cause. If the present state of a system is known in full detail, physics should be able to predict how that system will behave next. Without causes leading to effects, physics would lose much of its purpose. Without predictability, scientific progress would stall.

Guided by this principle, physics has achieved remarkable success. It explains phenomena ranging from subatomic particles to the origins of the universe itself. Within that same universe exists the human brain, an organ capable of consciousness and deliberate decision-making. This coexistence creates an apparent contradiction.

At first glance, causal determinism seems to rule out free will entirely. If every molecule and electrical signal in the brain could be known with perfect precision, future choices should be predictable in advance. Under that view, choice appears to be an illusion.

However, physics itself introduces several complications that weaken this conclusion. These complications do not reject determinism outright, but they reveal limits in prediction and understanding.

The first complication comes from chaos theory. Some systems behave in simple and predictable ways. Others, such as weather systems or double pendulums, are extraordinarily sensitive to initial conditions. In chaotic systems, even the smallest measurement error rapidly grows into complete uncertainty about future behavior.

These systems remain fully deterministic, because causes still lead to effects. Yet they become practically unpredictable beyond short time spans. Determinism, in this context, does not guarantee foresight.

The second complication arises from quantum mechanics. At the subatomic level, outcomes cannot be predicted with certainty. Physics can only assign probabilities to possible results. Chance dominates experimental outcomes involving particles.

Quantum mechanics remains deterministic in its mathematical structure, but it introduces a fundamental layer of uncertainty. It cannot specify exactly what will happen, only what is likely to occur. Whether these probabilistic rules meaningfully influence neural activity or consciousness remains unresolved. Consciousness itself is widely considered an emergent phenomenon.

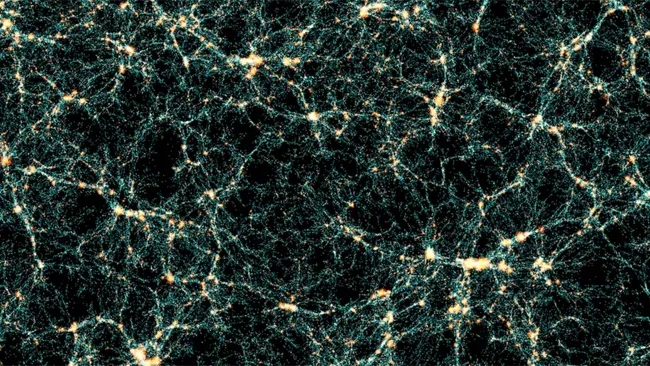

This leads to the third complication: emergence. Knowing the fundamental laws of nature does not automatically explain complex systems. Physics possesses an advanced theory of particle interactions, yet that theory does not explain how stars form or why certain flavors are enjoyable.

To understand complex systems, new frameworks and higher-level laws must be introduced. The same limitation may apply to the human mind. Brain activity may obey physical laws, yet conscious decision-making may require its own explanatory level.

None of these considerations delivers a definitive answer to whether free will exists. What they demonstrate instead is that physics has boundaries. Many philosophers support a position known as compatibilism. This view holds that free will and causal determinism are not mutually exclusive.

From this perspective, current physical theories may simply be incomplete when it comes to explaining choice and consciousness. A more advanced understanding of nature could one day reconcile determinism with meaningful agency.

In that sense, the question remains open. Physics does not clearly deny free will, nor does it fully explain it. For now, inquiry continues, driven by curiosity rather than certainty.