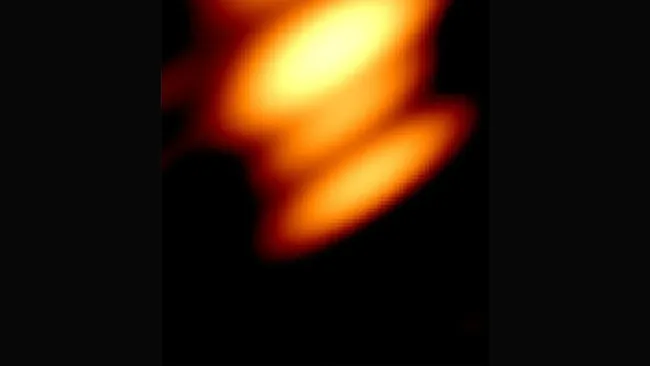

Astronomers have achieved a groundbreaking feat — capturing the first-ever radio image of two black holes orbiting each other, confirming a phenomenon long predicted but never before seen.

The newly released image shows a pair of supermassive black holes locked in a cosmic dance within the luminous quasar OJ287, located roughly 5 billion light-years away in the constellation Cancer. Quasars, the blazing hearts of galaxies, shine as gas and dust spiral into these gravitational monsters.

Researchers say this image provides the clearest visual evidence yet that binary black holes — two gravitational giants bound together — truly exist. “Quasar OJ287 is so bright it can even be detected by amateur astronomers,” said Mauri Valtonen, lead author from the University of Turku, Finland.

Quasars are among the brightest known celestial objects. While astronomers have previously imaged single black holes — such as those in the Milky Way and Messier 87 — none had ever been observed orbiting together until now.

Although gravitational wave detections have hinted at such pairs, direct visual proof was elusive due to the limited resolution of existing telescopes.

OJ287 has been observed for over a century — appearing even in photographs from the late 1800s, long before scientists could imagine the existence of black holes or quasars. The quasar began gaining attention in 1982, when Finnish astronomer Aimo Sillanpää discovered its light fluctuated on a 12-year cycle, suggesting the presence of two orbiting black holes feeding on surrounding material.

Now, that theory has been confirmed. Using combined observations from Earth-based telescopes and the RadioAstron (Spektr-R) satellite — a Russian space radio telescope that orbited halfway to the Moon — scientists achieved an image 100,000 times sharper than standard optical views.

When researchers compared the data to theoretical predictions, “the two black holes were exactly where they were expected to be,” the study stated.

“The black holes themselves are perfectly black, but we can detect them through their particle jets and glowing gas,” Valtonen explained. The image also revealed a twisting jet from the smaller black hole, resembling “a rotating garden hose,” caused by its rapid orbit around the larger one.

This jet is expected to sway back and forth like a cosmic tail as the smaller black hole completes its 12-year orbit, allowing astronomers to watch this celestial motion unfold in real time — a phenomenon never before witnessed.

The discovery is detailed in a paper published on October 9 in the Astrophysical Journal, marking a historic breakthrough in the study of supermassive black holes and binary cosmic systems.