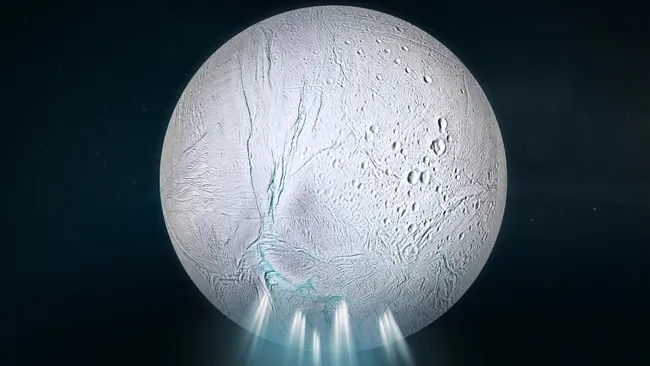

Saturn’s moon Enceladus is shooting out organic molecules that could help create life. Complex organic molecules were found in the watery geysers of Enceladus, almost twenty years after they were first sampled by NASA’s Cassini spacecraft.

Although Cassini’s mission ended in 2017, scientists continue to uncover new findings within its vast archive of data. The discovery of these organic molecules strengthens the case for Enceladus as a body of astrobiological interest.

In 2005, Cassini detected plumes of water vapor spraying into space from large fissures on Enceladus’ surface. These fissures are believed to lead to a hidden subsurface ocean within the 500-kilometer-wide moon. Most of the plume material escapes into space, forming Saturn’s diffuse E-ring, while some falls back onto the moon’s surface.

“Nozair Khawaja of Freie Universität Berlin and the University of Stuttgart explained that Cassini constantly sampled ice grains in Saturn’s E-ring, detecting various organics, including amino acid precursors.”

However, debate persisted over whether these molecules originated from Enceladus’ ocean or were produced by radiation in Saturn’s magnetosphere. To clarify, Khawaja’s team revisited Cassini’s Cosmic Dust Analyzer (CDA) data from 2008. Their detailed reanalysis revealed overlooked organic molecules within plume samples.

When Cassini flew through the plumes, icy grains struck the CDA detector at 18 kilometers per second. This high speed prevented water molecules from clustering, allowing organic signals to appear more clearly. The findings confirmed that the same organics found in the E-ring also exist in the plumes, meaning they must originate from Enceladus’ ocean.

The newly detected molecules include aliphatics, heterocyclic esters, ethers, and possibly nitrogen- and oxygen-bearing compounds. On Earth, these substances play roles in chemical pathways leading to life. “There are many possible pathways from the organic molecules we found to life-related compounds, which enhances the likelihood of habitability,” Khawaja said.

Yet, caution remains. Grace Richards of INAF in Rome suggested radiation could also create organics on Enceladus’ surface near fissures, potentially confusing results. This raises doubts about whether organics detected in the plumes truly come from the ocean or from radiation effects.

The only definitive way to resolve this uncertainty is to land on Enceladus and directly sample its fresh ice. The European Space Agency is considering such a mission, with an orbiter-lander combo expected by 2054.

The new findings from Cassini’s Cosmic Dust Analyzer were published on October 1 in Nature Astronomy, further fueling interest in Enceladus as one of the most promising places in the search for extraterrestrial life.