With over 6,000 exoplanets now confirmed, astronomers are gearing up for a new era of discovery. Over the next three decades, planet hunters expect tens of thousands more worlds to be identified as new detection techniques come into play and major space missions prepare for launch.

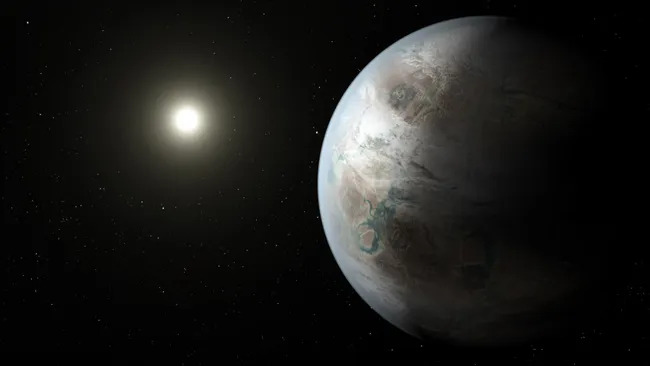

“We’ve found 6,000 planets, but none like Earth,” said Aurora Kesseli, an astronomer at Caltech working with NASA’s Exoplanet Archive, in an interview with Space.com. “The reason we keep looking is because we haven’t found an Earth-like planet yet. But several upcoming missions are specifically designed to do just that.”

Among these, the European Space Agency’s PLATO mission will lead the charge in December 2026, aiming to detect transiting, rocky worlds within the habitable zones of their stars. Following closely, NASA’s Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope will launch in 2027, joining PLATO and JWST at the L2 point to search for planets via gravitational microlensing.

In 2028, China’s Earth 2.0 mission will join the effort, also targeting transits of Earth-sized planets orbiting sun-like stars. With NASA’s TESS still active, astronomers anticipate a tidal wave of new planetary discoveries.

Kesseli and her colleagues at the Exoplanet Archive are preparing for the data surge. “The challenge will be handling the sheer numbers,” she said. “From PLATO, Earth 2.0, and the Roman Space Telescope, we’re expecting roughly 100,000 transiting planet candidates.”

The ESA Gaia mission will also deliver thousands of new worlds by the end of 2026 using astrometry, a technique that measures subtle positional shifts in stars caused by orbiting planets. “We currently have fewer than 10 planets discovered this way,” said Kesseli, “but Gaia’s sensitivity will change that dramatically.”

Meanwhile, the Roman Space Telescope is expected to detect around 2,000 microlensing planets—many in the distant galactic bulge. While follow-up studies will be limited, these findings will help astronomers estimate how common Earth-like planets truly are.

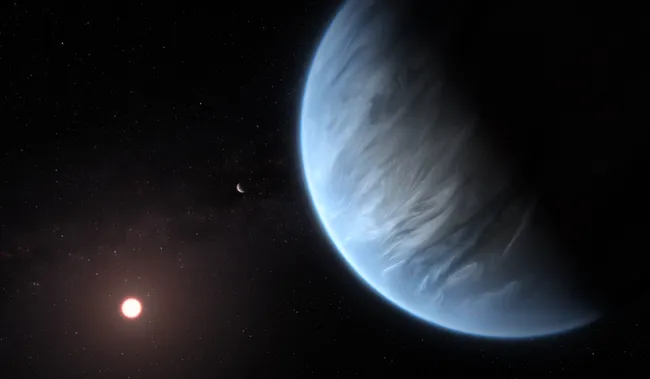

The next wave of exploration won’t stop at discovery. The late 2020s will see the launch of ESA’s ARIEL mission, designed to conduct a large-scale survey of exoplanet atmospheres. “It will focus on Neptune- and Jupiter-sized worlds,” said Kesseli, “but it’ll give us a baseline for understanding atmospheric diversity.”

JWST is already probing the skies for signs of life-friendly atmospheres, particularly around nearby red dwarfs such as those hosting the TRAPPIST-1 planets. While results so far remain inconclusive, astronomers are optimistic that longer observations and better techniques will soon yield answers.

Yet, observing an Earth analog around a sun-like star remains beyond JWST’s sensitivity—and even next-generation 30-meter ground telescopes may fall short. “If we want to actually see an Earth-like planet around a sun-like star, we’ll need the Habitable Worlds Observatory,” Kesseli explained.

Planned for the 2040s, HabEx will feature an eight-meter mirror and a starshade coronagraph to block starlight, allowing direct imaging of distant worlds. Scientists hope it could reveal oceans, continents, vegetation—or even signs of civilization.

The first 30 years of exoplanet science were about discovery; the next 30 will focus on characterization. With missions like PLATO, Roman, ARIEL, and HabEx, humanity may soon uncover the first truly Earth-like planet—a world that redefines our understanding of life’s place in the universe.