Astronomers using the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) have found strong evidence for a potential new exoplanet orbiting Alpha Centauri A, the nearest sun-like star to Earth. The system is located just four light-years away, within the Alpha Centauri triple-star system.

Using JWST’s Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI) with a coronagraphic mask to block the stars’ glare, the team was able to detect much fainter objects. This technique revealed a possible planet about 10,000 times fainter than Alpha Centauri A.

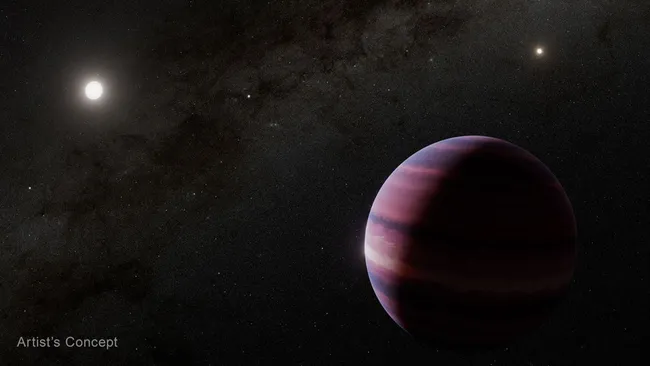

The candidate planet lies within Alpha Centauri A’s habitable zone, where liquid water could theoretically exist. However, it is a gas giant, making it unsuitable for life as we know it. Still, its discovery is significant, reminiscent of the fictional moon Pandora from the “Avatar” film series, which orbits a gas giant around Alpha Centauri A.

Scientifically, the find is even more remarkable. At a distance of just two astronomical units from its host star — twice the Earth-Sun distance — it could be the closest planet to its star ever imaged. It would also be the first planet imaged around a star with both age and temperature similar to the Sun.

“With this system being so close to us, any exoplanets found would offer our best opportunity to collect data on planetary systems other than our own,” said Charles Beichman, executive director of the NASA Exoplanet Science Institute at Caltech and senior scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

Currently, the Alpha Centauri system hosts two confirmed exoplanets, both orbiting the red dwarf Proxima Centauri. Confirmation of the Alpha Centauri A gas giant remains pending, as follow-up JWST observations did not yield further evidence. Simulations suggest the planet might have been too close to its star to be detected.

Researchers hope future observations from JWST and the upcoming Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope, launching in May 2027, will provide the confirmation needed.

“The very existence of such a planet in a system with two closely separated stars would challenge our understanding of how planets form, survive, and evolve in chaotic environments,” said Aniket Sanghi, a Caltech graduate student who co-led the study with Beichman.

The findings have been detailed in two papers accepted for publication in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.