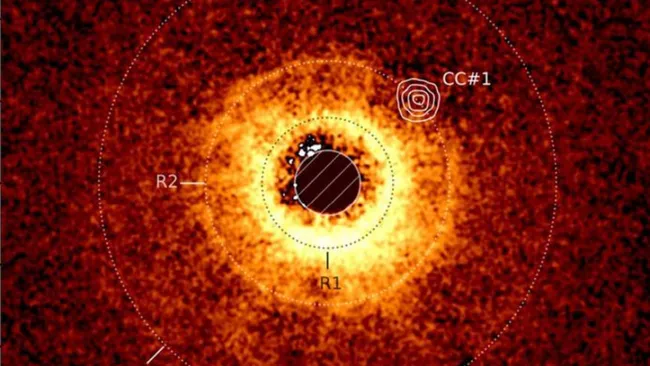

A pair of colliding spiral galaxies, NGC 5713 and NGC 5719, may provide a glimpse into the Milky Way and Andromeda’s future merger. Located 88 million light-years away, these galaxies are now about 300,000 light-years apart, steadily approaching each other.

Astronomers observed that their dwarf galaxies are transitioning into a co-rotating plane, instead of orbiting randomly. This discovery challenges the standard model of cosmology, which predicts a scattered, cloud-like distribution. Fourteen dwarf galaxies in the system have been confirmed, with 18 more awaiting verification.

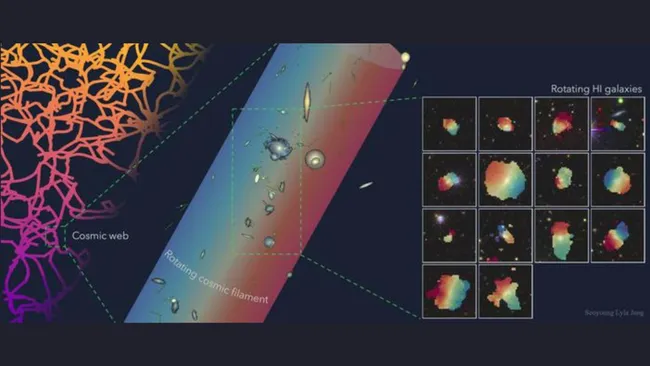

Sarah Sweet, from the University of Queensland, explained that the satellites once orbited in a cloud-like structure but are now flattening into a tube-shaped distribution. The process may have been influenced by the Boötes strip, a filament of dark matter in the cosmic web.

This mirrors the puzzle around the Milky Way and Andromeda, whose dwarf galaxies also align in planes. However, unlike NGC 5713 and NGC 5719, the Milky Way and Andromeda have not yet interacted directly. Astronomers suspect past mergers shaped these patterns, especially in Andromeda.

The Milky Way’s history remains less clear, as its last major merger occurred between 8 and 11 billion years ago. Cosmological simulations still struggle to replicate such planes of satellites, raising questions about the standard dark matter model. Some suggest alternative gravity theories, while others argue current models need refinement.

Ultimately, studying colliding galaxies like NGC 5713 and NGC 5719 helps astronomers predict the outcome of the Milky Way-Andromeda merger, expected in about 4 billion years. Future Hubble observations may further unravel the mystery of dwarf galaxy orbits and reshape our understanding of cosmic evolution.