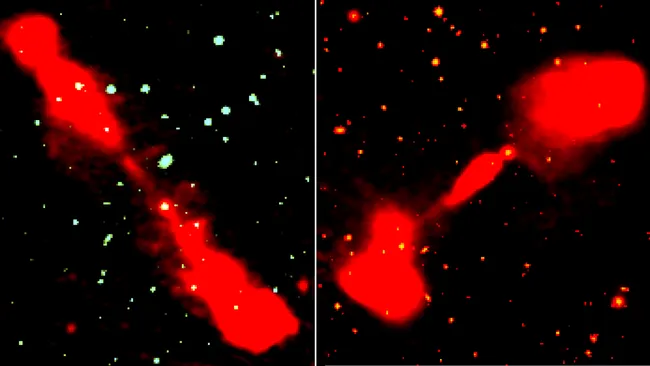

Astronomers have traced a massive cosmic explosion back 12 billion years, marking the most distant event where escaping starlight was directly observed.

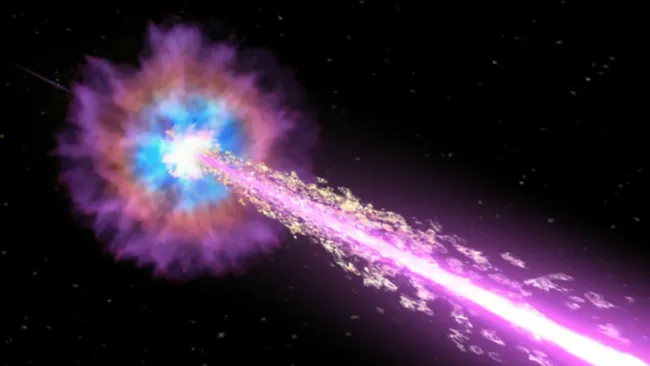

The phenomenon belongs to a mysterious class of outbursts known as Fast X-ray Transients (FXTs), which last only minutes. Using the Einstein Probe X-ray space telescope, scientists pinpointed one FXT, EP240315A, which traveled towards Earth for 12 billion years.

“We’ve known these unique explosions exist, but now, thanks to the Einstein Probe, we can locate them in near real time,” said team member Peter Jonker of Radboud University.

FXTs occur in galaxies billions of light-years away, lasting from seconds to hours. Scientists have long theorized FXTs might be tied to massive stars collapsing into black holes.

“This event is novel because only a few FXTs had been found before, mostly in archival data,” said Samantha Oates of Lancaster University. “By discovery, follow-up studies were usually too late.”

To map EP240315A, astronomers combined data from the ATLAS telescope system, the Very Large Telescope (VLT) in Chile, and the Gran Telescopio Canarias in Spain.

“These observations show the explosion happened when the universe was less than 10% of its current age,” said Andrew Levan of Radboud University. “It released more energy in seconds than the Sun’s entire life.”

FXTs may be related to Gamma-ray Bursts (GRBs), the most powerful explosions known, caused by massive stars dying and forming black holes. Unlike FXTs, GRBs have been studied for half a century.

Jonker noted: “Many FXTs might come from GRB-like systems, but much more diversity likely exists.”

VLT data revealed EP240315A’s source lacked hydrogen, which normally blocks ultraviolet light. Around 1.8 billion years post-Big Bang, escaping UV light ionized surrounding hydrogen.

“Roughly 10% of UV light from the host galaxy may have escaped to ionize the universe,” said Andrea Saccardi of CEA Saclay. “This is the most distant event where escaping starlight is directly seen.”

EP240315A was among the first detected by the Einstein Probe, launched in January 2024. Since then, over 20 FXTs have been identified.

“The Einstein Probe is revolutionizing FXT research, opening a new window to study massive star deaths and early-universe conditions,” Oates concluded.

The research was published on August 19 in Nature Astronomy.