A groundbreaking study from the University of Technology Sydney (UTS) finds that lunar dust is significantly less toxic to human lungs than the air pollution found on Earth’s busy streets.

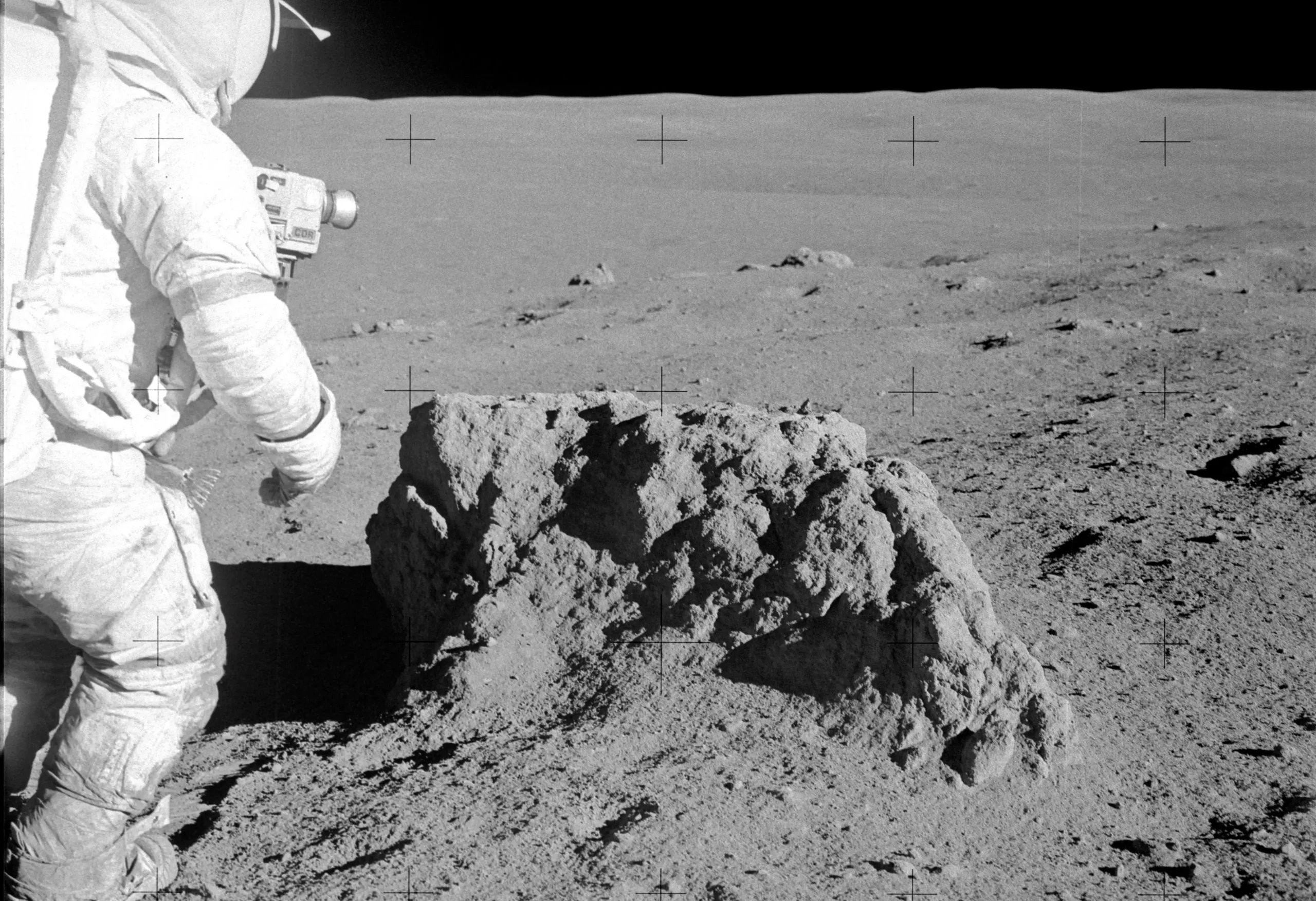

Published in Life Sciences in Space Research, the study offers timely reassurance for NASA’s Artemis program, which seeks to re-establish a sustained human presence on the Moon. The research tested how advanced lunar dust simulants affect human lung cells compared to fine particulate matter from a congested Sydney street.

While moon dust particles can irritate the lungs, they do not cause the same cellular damage or inflammation typically linked with urban air pollutants. The research team used 2.5-micron-sized dust particles, small enough to penetrate deep into lung tissue.

Lead researcher Michaela B. Smith, a PhD candidate at UTS, noted historical concerns dating back to the Apollo missions, when astronauts reported respiratory issues after contact with lunar dust. “Any dust you inhale will irritate the lungs,” Smith said. “But lunar dust isn’t like silica dust from construction sites that leads to silicosis. It’s irritating, yes—but not dangerously toxic.”

Lunar Dust vs. City Air

Lung cells from both the bronchial and alveolar regions were exposed to the dust. Earth-based pollution triggered more intense inflammation and toxicity, while lunar simulants did not induce oxidative stress—a key mechanism of fine particle damage.

“If moon dust exposure happened at levels found in Earth’s urban air, health impacts would likely be minimal,” the researchers concluded.

NASA’s Mitigation Strategy

Despite the relatively lower risk, NASA continues to develop dust control measures. Smith observed promising designs at NASA’s Johnson Space Center, where spacesuits remain docked to the rover’s exterior to prevent moon dust from entering spacecraft cabins.

Smith’s doctoral research goes even further—studying how microgravity affects lung function. Using lab devices that mimic weightlessness, her team investigates long-term lung cell behavior in space-like conditions.

Australia in the Space Race

Co-author and Smith’s supervisor, Distinguished Professor Brian Oliver of UTS and the Woolcock Institute of Medical Research, emphasized the study’s global impact.

“These results support the safety case for returning to the Moon,” said Oliver. “They also place UTS at the forefront of space life sciences in Australia.”

With lunar missions ramping up and concerns about astronaut health still paramount, studies like this are crucial for future human space exploration. For now, it seems the Moon is a little less hostile than previously imagined.