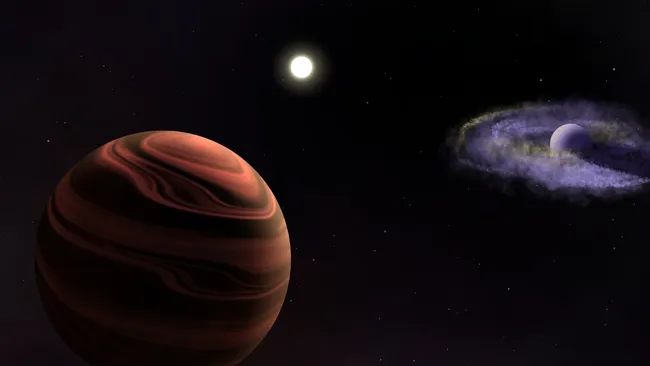

The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) has captured an unprecedented cosmic phenomenon: a distant planetary system 300 light-years away where one gas giant rains sand, and its partner is literally building a “sandcastle.”

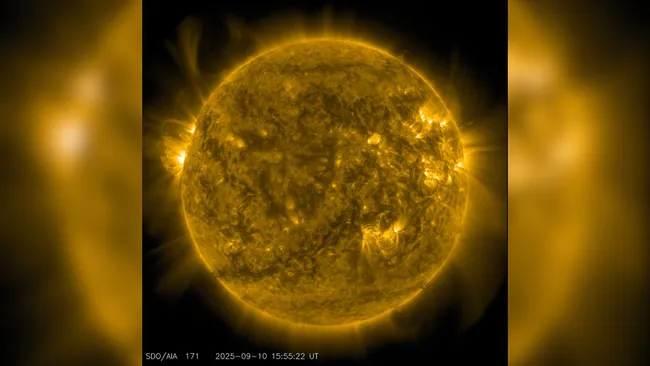

The system, called YSES-1, orbits a star only 16.7 million years old—cosmically young compared to our 4.6 billion-year-old Sun. It hosts two planets: YSES-1 b and YSES-1 c. Both are gas giants embedded with silicate materials, offering researchers a new opportunity to study how planets evolve in real-time.

Astronomers note that this discovery could provide essential insights into how planetary bodies—including those in our solar system—took shape. According to Valentina D’Orazi from Italy’s National Institute for Astrophysics (INAF), “Observing silicate clouds, which are essentially sand clouds, in the atmospheres of extrasolar planets is important because it helps us better understand how atmospheric processes work and how planets form.”

She further explained that these clouds are sustained by a process similar to Earth’s water cycle—sublimation and condensation—but composed of sand-like silicates. This breakthrough provides vital clues about chemical transport and climate modeling in non-Earthlike conditions.

A Planet That Rains Sand

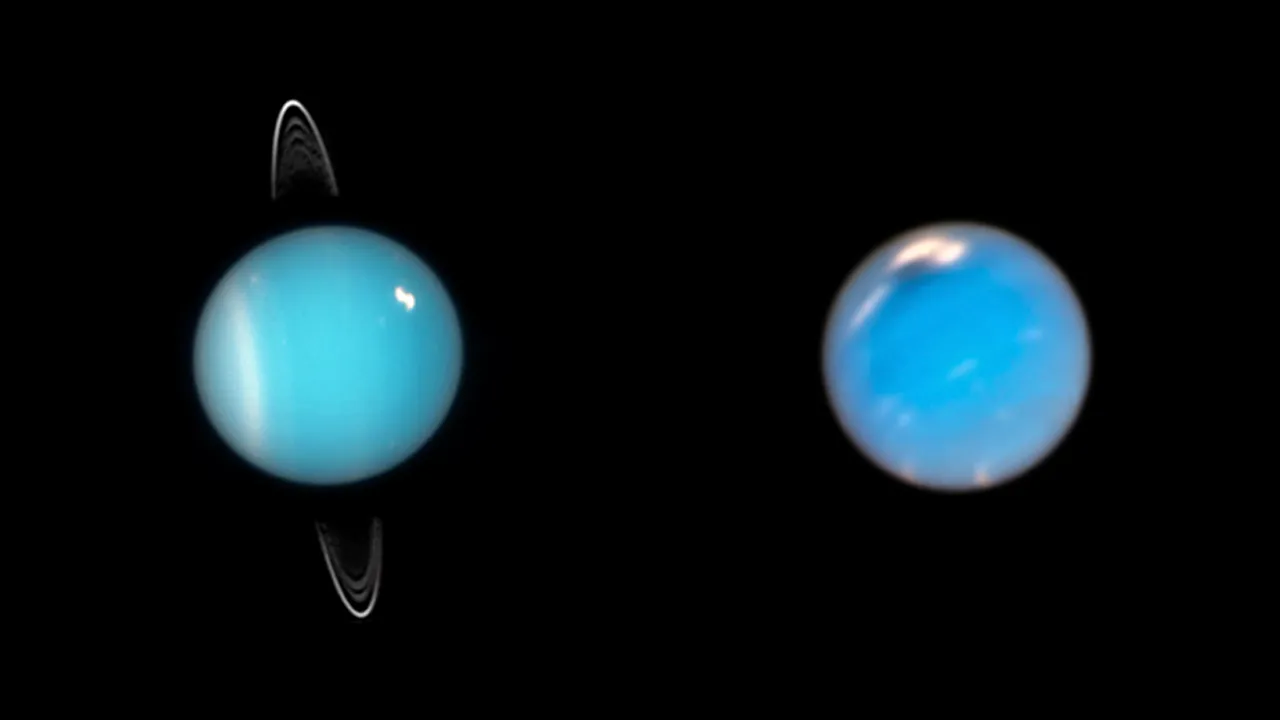

YSES-1 c, roughly 14 times the mass of Jupiter, features reddish sand clouds made of iron-rich pyroxene or a mix of bridgmanite and forsterite. These clouds rain silica material downward toward the planet’s core—essentially creating a “sandstorm” world. This marks the first time such silica clouds have been directly observed in the atmosphere of an exoplanet.

Building a Cosmic ‘Sandcastle’

Meanwhile, YSES-1 b, with six Jupiter masses, is still forming. It’s surrounded by a circumplanetary disk, a flattened cloud of matter that feeds material—including silicates—onto the growing planet. The ongoing accumulation of silicate material has drawn comparisons to “sandcastle building,” a poetic metaphor for planetary birth.

What makes this even more remarkable is that this marks the first detection of silicates not only in exoplanet atmospheres but also in a circumplanetary disk.

These findings extend our knowledge of planetary systems beyond our own and suggest that dynamic, dusty processes could be more common in young planetary environments than previously thought.

Thanks to the powerful vision of the James Webb Space Telescope, researchers can now peer into worlds undergoing dramatic and alien weather patterns—worlds that could never host human life, but that hold the key to understanding our cosmic origins.